Crunching the numbers on Spanish Flu in Raikeswood Camp

Harriet Purbrick, a final year History student at the University of Leeds, has conducted an analysis of the Spanish Flu figures for Raikeswood Camp as part of her Laidlaw Scholarship work:

The so-called Spanish flu struck Skipton POW camp in February and March 1919, killing 47 German prisoners. The historian Panayi, writing about sickness in both military and civilian internment camps in the UK during the First World War, singles out Skipton as “one of the camps hardest hit” by the influenza epidemic (Prisoners of Britain, p. 131). Five POWs were hospitalised with influenza in November-December 1918 but this pales into insignificance compared to the contagiousness and deadliness of the spring outbreak, as illustrated in more depth by the data below.

Methodology

There are three ways to identify a case of influenza in the camp. Firstly, ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) records show when a Skipton POW was admitted to or discharged from hospital (appendix I) and provide a brief description of their illness: almost all prisoners were marked with “influenza and pneumonia”. The ICRC also records POW deaths and states the cause of death. Secondly, Keighley War Hospital records show when POWs were admitted to or discharged from hospital.

Lastly, a book, Kriegsgefangen in Skipton (1920)*, written by Skipton POWs and smuggled out of the camp contains a chapter on the “influenza epidemic” and features statistics on the numbers of symptomatic cases, deaths and hospitalizations of officers and men (below). It also contains a sketch of a memorial which names all the officers and men who died and were buried at Morton Cemetery in Keighley.

* English translation contained within German Prisoners of the Great War: Life in a Yorkshire Camp (2021)

Statistics

| All POWs | Officers | Men | |

| Total interned in Skipton camp (February 1919) | 683 | 546 | 137 |

| Flu symptoms | 371 (54%) | 324 (59%) | 47 (34%) |

| Hospitalisations | 91 (13%) | 74 | 17 |

| Survived after hospitalisation | 49 (7% of total, 54% of hospitalised) | 42 | 7 |

| Deaths | 47 (7% of total, 13% of symptomatic) | 37 | 10 |

| Died in hospital | 42 (6% of total, 46% of hospitalised) | 32 | 10 |

| Died in camp | 5 (0.7% of total, 1.3% of symptomatic) | 5 | 0 |

Source: German Prisoners of the Great War: Life in a Yorkshire Camp, p. 216.

NB: percentages have been rounded to the nearest integer where appropriate.

Perhaps the most engaging statistic from the table is that a prisoner who went into hospital with flu only had a slightly higher chance of survival (54%) than death. Yet, the records do not show how long the prisoners had been sick for before they were admitted. By the time they were sent to hospital they were probably already seriously ill. In fact the medical records for all the POWs admitted with Spanish flu stated they were suffering from pneumonia as well as influenza. The book chapter explains that prisoners in the camp hospitals faced many obstacles before the English administration would admit them to an external hospital, for instance a Skipton hospital refused to accommodate the prisoners and when space became available at Keighley, there were long delays due to transport issues.

Of all the prisoners who fell sick (symptomatic), around 13% died.

The officers and men who died are named in the book Kriegsgefangen in Skipton, and the memorial separates out the two military groups, first listing the names of the deceased officers in alphabetical order followed by the men. It can be seen that a higher proportion of officers than men became sick.

Tracking the outbreak

The chapter on the influenza outbreak states that the outbreak began on 12 February 1919, when five orderlies fell ill with flu symptoms. It spread further among the orderlies (who were housed in more cramped dormitories than the officers) before the first officers fell sick on 15 February. The symptoms started with a few days of tiredness and a lack of appetite (leading to constipation), followed by a sudden outbreak of fever, which peaked on the fourth or fifth day, and was accompanied by a high temperature, shivering and a headache. Some prisoners also suffered from coughing, nose bleeds, body aches and, more rarely, ear infections. Whilst most prisoners began to recover after their fever peaked, some suffered complications, such as pneumonia and other lung as well as heart problems due to nerve and tissue damage.

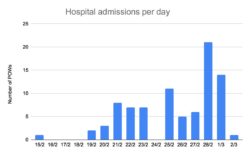

This encompasses all the POWs admitted to hospital – except one who was admitted on 25th March – whether they were discharged or died.

The above chart shows that there was a smaller wave of admissions around 21 February, followed by a much larger one at the end of February. This means that the vast majority were hospitalised in the same two weeks.

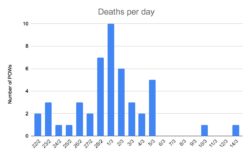

Sample: 47 men . This corresponds to the 42 who died in hospital and the five prisoners who died in camp.

Unsurprisingly, deaths lag a few days behind hospital admissions.

1 March is an obvious climax of the outbreak, with a very high hospital load of influenza patients and the highest number of deaths on any day by some margin.

The prisoners were all buried a few days after their deaths at Morton Cemetery in Keighley. However, after the governments of Britain and West Germany agreed in 1959 to transfer the remains of all German military and civilian personnel from both world wars to a single cemetery under the authority of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The prisoners’ graves were transferred to Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery in Staffordshire, alongside nearly 5000 other burials.

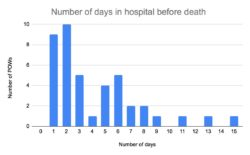

Sample: 42 men (five died in camp)

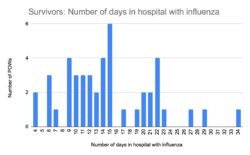

The sharpest contrast in the data is the length of hospital stays between those who died and those who survived. Whilst 19 POWs died within the first one or two days – and no one lasted more than 15 days – the average hospital stay for survivors was around two weeks. However, two POWs had much longer stays, at 83 and 66 days (omitted from graph below).

Sample: 45 POWs (2 omitted, 2 have not been matched with their files).

Cause of death

Almost all the POWs had influenza and pneumonia recorded as their cause of death. For three officers, their deaths were attributed to influenza and heart failure. However, ICRC records (appendix III) show that for two of these officers, their cause of death was “amended” a few months later to influenza with either pneumonia or pulmonary complications.

Re-admission to hospital

A few prisoners who contracted influenza were later re-admitted with lung problems. For example, Heinrich Flügge, who spent 21 days in hospital with influenza and pneumonia in March was re-admitted on 6 May with a complication of flu: pleurisy with effusion (inflammation of the lining between the lungs and ribs). He spent another 27 days in Keighley War Hospital. Similarly, Martin Most – who spent a whole 83 days in hospital with influenza, including an operation for empyema about a month in – returned in early July, also with pleurisy, and a recurrence of empyema.

Meanwhile, another prisoner, Henry Schriefer was re-admitted just 12 days after being discharged, suffering from “general debility.” Weekly records track his “satisfactory” progress until he was discharged four weeks later.

A few other prisoners were not re-admitted to hospital but were nonetheless noted for being “very poorly” during their recovery in camp.